The bank failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank were significant economic events. These failed banks were taken over by the FDIC on March 10th and 12th, respectively. Regulators worked to calm the market on March 12th by issuing a statement that the banking system, “remains resilient and on a solid foundation.”

To really understand what is happening, let’s examine the banking data directly. Recently released figures now allow for a look at how banks are actually handling the situation. This makes it possible to assess the level of stress remaining in the banking sector.

Direct borrowing from the Fed suggests the risk of bank failures has not been resolved

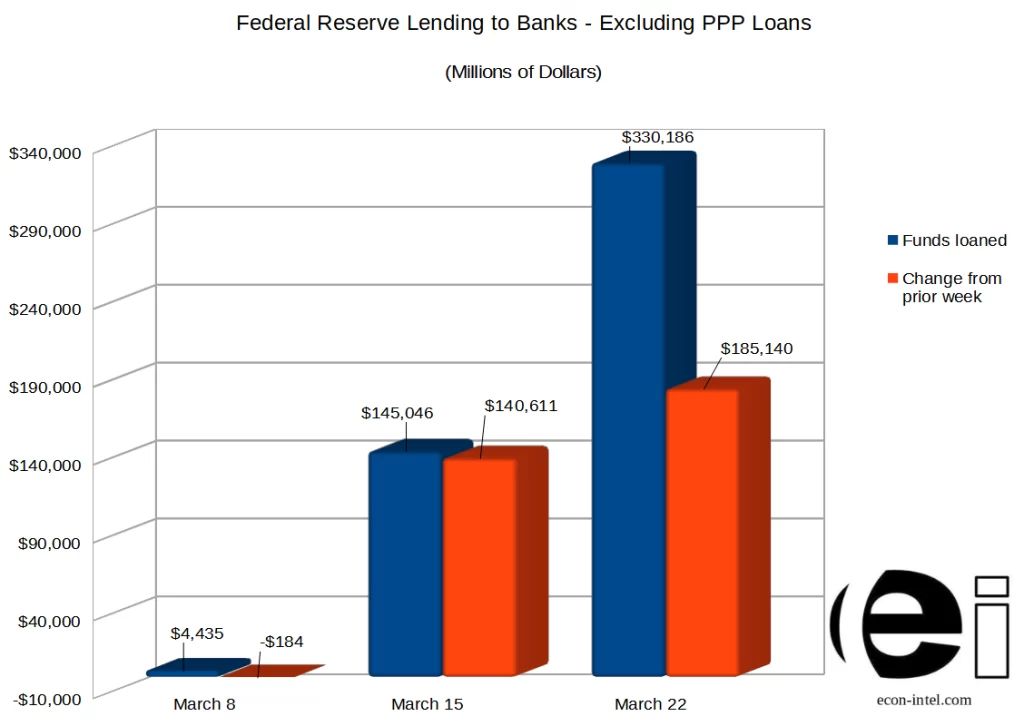

Leading up to and through the bank failures, one would expect banks to borrow more money. However, once the crisis had passed and the assurances had been made by the authorities, there would be no need for banks to borrow even more money.

Borrowings not only increased, but increased more than the week of the failures. Banks pay interest on borrowed funds and would not borrow money without cause. It makes sense for a bank to borrow, if it can invest the money at a rate higher than the cost of borrowing. This is unlikely to be the case in the current interest rate environment. Due to the Fed’s rate increases, the cost to borrow exceeds the rate of return on safe investments.

The other reason that a bank would borrow is if it had to raise cash to meet depositor demand. This is more likely what is happening.

A reasonable possibility is that depositors at certain banks are withdrawing, or simply spending down their accounts. This in turn may lead to some banks that are required to borrow to provide depositors access to their funds.

Borrowing money from the Fed eliminates the need for banks to sell their bonds. This is a convenient solution because banks do not have to recognize losses on their bonds below par value. However, the bank also must pay interest on borrowed funds. This will cut into their profitability.

Economic backdrop

The data above is direct evidence of financial stress in the banking sector. However, keeping the full economic and regulatory environment in view will help provide the clearest picture possible.

The failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and Credit Suisse destroyed significant wealth. Tens of billions of dollars of equity and bonds were erased from the market. The fall out from this destruction of wealth may not have made its way through the economy yet. Will this force some of their investors to liquidate part of their bank accounts to cover payments? Or could another bank have lost enough from holding stocks or bonds of these failed banks that writing them off makes it insolvent as well? These are difficult questions to know for sure, but it is quite possible that there could be lingering effects.

Regulatory backdrop

Changes made by the Federal Reserve mean that banks no longer need reserves to meet regulatory requirements. The Fed refers to this as an Ample Reserve Regime. What it actually means is that there is no longer a requirement for a bank to hold any portion of your deposits in cash or on deposit at the nearest Fed branch. This allows banks to invest up to 100% of your deposits. If their investments decline, there is no liquid buffer under the Ample Reserve Regime, to provide for depositor funds. Likewise, if more people spend or withdraw their money than the bank anticipated, the bank will run short on cash.

The Federal Reserve eliminating the requirement that banks hold reserves ushers in a new era in bank regulation in the U.S. This experiment has only been in place since March 26th, 2020. Until very recently, the banking system had been relatively flush with cash. In response to the 2008 crash and the coronavirus, the Fed pumped out fresh money. This money found its way into the banking system. Now that the Fed has begun removing money, we may find out that at least some banks did not maintain adequate reserves and are in trouble.

Risk of bank failures – kickers

The $330 billion that banks are borrowing from the Federal Reserve is less than the all-time record for borrowing from the Fed. This record was set the week ending October 15, 2008 at almost $438 billion. However, there is an enormous difference between what these numbers measure. It is not an apples to apples comparison. In 2008, regulations required banks to hold reserves. If their reserves fell below the reserve requirement, they could borrow the difference from another bank or the Federal Reserve. Meaning banks borrowed to meet their reserve requirements. In other words, borrowing meant that the bank was having trouble maintaining reserve levels. Not that it was out of cash.

Today there is no reserve requirement. So, banks do not need to borrow until they are in need of immediate funds. True, a bank could borrow to make investments or borrow to avoid selling a security at a loss. But, as touched on above, the likelihood of borrowing for investment is low. This is especially true given the high levels of borrowing we are currently seeing. Additionally, if history serves as a guide, banks borrow very little from the Fed except in times of crisis.

In 2008 it wasn’t just banks borrowing

Additionally, the $330 billion of borrowed funds at this time all represents banks borrowing. The $438 billion represented loans to banks, money market funds, and other financial institutions. So, while the amount in 2008 was greater, it was not higher within just the banking sector.

It is too early to conclude that the banking crisis is over. We will see how the reassurances of a “sound and resilient” banking sector age. Perhaps no better than the term “transitory inflation” has.

Until lending from the Fed to the banks subsides, there are likely bank liquidity concerns lurking behind the scenes.

Update on 3/31/23: Data released yesterday indicates that bank borrowings from the Federal Reserve (excluding PPP loans) declined approximately $11 billion from close to $344 billion on March 22nd to approximately $333 billion on March 28th. This is a positive sign that bank stress may be decreasing. However, bank borrowing from the Fed remains significantly elevated.

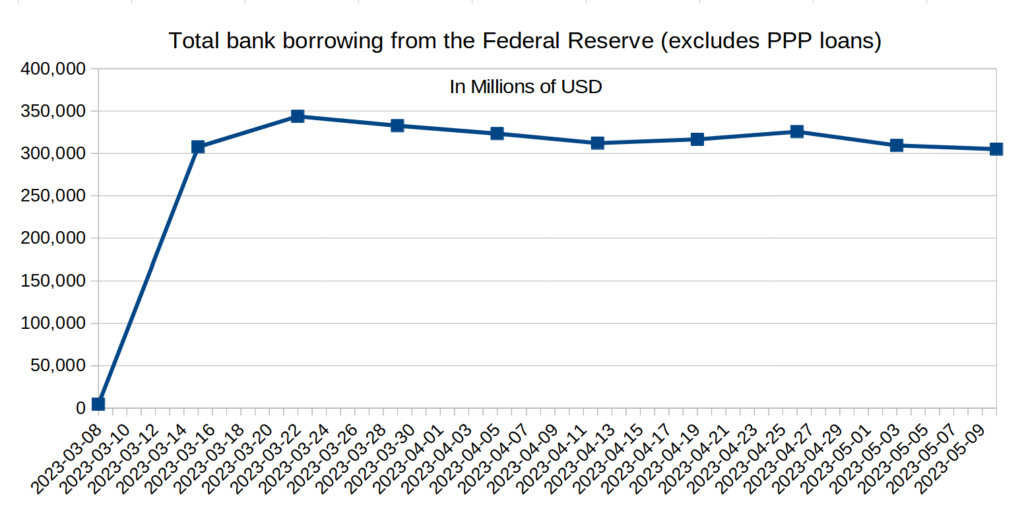

Update on 5/12/23: While loans from the Federal Reserve to banks have declined from their peak, the change remains minimal. We cautioned in the original article, shortly after Silicon Valley Bank failed, that we were skeptical of the soundness of the banking sector. Since that time, an even larger bank, First Republic, has failed. At this time, we still see little reason to believe that the financial stability of the banking system has improved significantly.

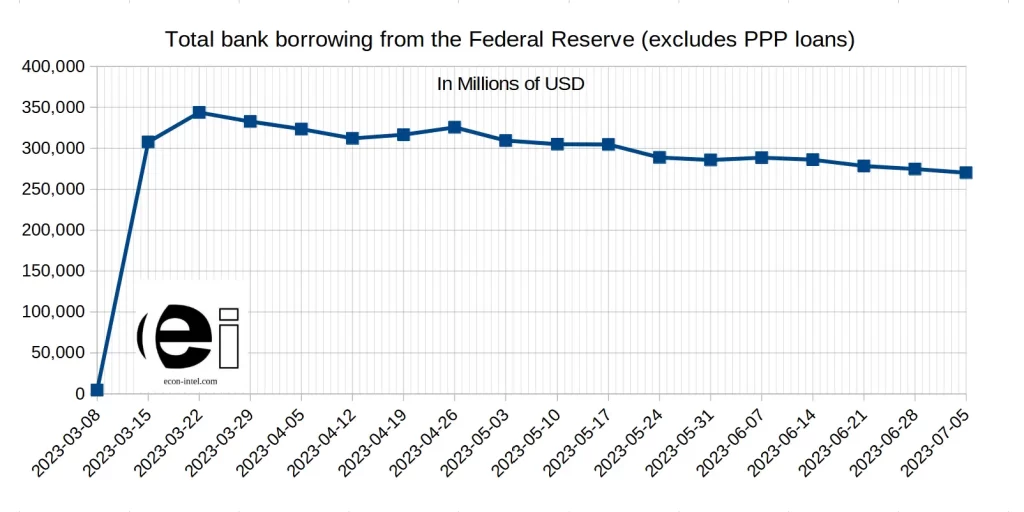

Here is bank borrowing from the Fed (excluding PPP loans):

Update on 6/5/23: At this point there is still little reason to believe that the banking system has recovered and stabilized. So that people can better protect themselves in the face of bank failures, we have assembled bank safety reports for every FDIC insured bank. Find the answer to the question, “Is my bank safe?”

Update on 7/7/23: At this point it appears that the downward trend in banks borrowing from the Fed has been established for a long enough period of time that one could reasonably believe that the banking crisis is resolving. With that said, the incredibly slow pace returning to the baseline is clearly apparent. This leaves little doubt that significant stress remains with at least some of the banks. This also implies that a significant shock to the industry could kick off the bank failure crisis again.